Hidden histories, that what I’m into and also that’s what makes my soul tick. Trying to make the past and its many dead come back to life, even putting the clothes and skin back on their decaying bones – and letting their lives be known to our current, media and information-hungry society. For nearly thirty years of my life I’ve delved into trying to resurrect the once massive diaspora of the German-Queensland farming community’s culture, its music, folklore and the many earthy people. Some may call them peasants, but to me their love of the soil and the new land was engrained in their being. Like many species of our unique fauna and flora, this culture and its remaining baggage is now almost extinct. My last decade of working has taken me from my beloved Toowoomba to places like Brisbane, Gold Coast Wollongong and Roma. Each of these places had its hidden ‘German histories’ – often swept under the carpet by the dominant Anglo-culture, particularly when controlled by Anglophiles. Now I’ve recently arrived in Sydney. Taking up my position as a bushfire specialist with a prominent North Shore council I’m now just starting to find my elusive treasure in the suburbs – specifically the German people who shaped our amazing continent in so many ways. I want to tell you an amazing story of one such family. Not far from where I work in suburban Gordon is a most small yet charismatic reserve – dominated by massive Blue-gum and Stringybark trees with a small meandering creek clad with tree-ferns and other gems. This shady cleft, on my council database and maps it is called Orana Reserve – a generic Aboriginal name meaning ‘welcome’. However, the beautiful little patch of remnant bush has a far more fascinating background. Before the ‘Great War’ (1914 – 1918), the fashionable North Shore was even then multicultural – and had a large number of German wool-buyers residing in the leafy suburbs. Their job was to procure the wool off the sheep’s back and send the bales to far-off Germany for processing in the countries huge woollen mills, which employed tens of thousands of factory workers to make the garments to fend off the icy cold northern-hemisphere winters. Names like Beinssen, Metzler, Schreiterer and Lohmann were then respected German families in the basically English-dominated suburbs. Then came 1914 and tensions soon developed. With these troubled times came angst and paranoia, turning once friendly neighbourhoods into areas of hatred where racial resentments ran high. For instance in 1917 the large family home of Paul Schreiterer, ‘Bangoola’, was torn apart in a drive-by bombing using gelignite. New South Wales had over thirty branches of the Anti-German League established – and the local Mosman branch was one of the most active in seeking out suspects amongst the once highly respected ‘German wool buying’ fraternity. Many false and foolish accusations were made of the activities of any non-Anglo European minority group – particularly if from parts of the greater German Empire. The now leafy suburb of Pymble, now fragmented by the busy Pacific Highway and Mona Vale Road, still holds many magnificent residential relics of times long past. “Lanosa” is no exception. Today situated on busy Mona Vale Road, this beautiful house was originally called Te Whare and built in 1897. In 1919 the stately mansion became the home of German immigrant and his Australian wife, Mabel (nee Smith) and three daughters – Louise, Suzanne and Margot. Albert changed the name to Lanosa – meaning ‘wool’ in Portugese. Albert Emile Reichard was born in the disputed German-French territory of Alsace-Lorraine in July 1872 in the German town of Erstein. He was German-born at a stage when Alsace-Lorraine was annexed to Germany. His family were of well-to-do German origins and affiliations, both owning and managing large woollen mills in the rural area. At the age of 20, Albert emigrated to Australia, accepting a commercial position in the burgeoning wool industry. Every few years Albert returned to Germany to see his family. In February 1918 he was appointed Commonwealth Wool Appraiser and also was manager of the Australians operations of an international firm of wool traders, Simonius and Vischer and then soon after purchased Te Whare. Towards the end of World War 1, Albert was accused by the Commonwealth Government of ‘aiding the enemy’ by work colleagues. He was found to have spoken to two separate German wool dealers (Wedemeyer and Dreiheller) on two occasions in the Botanic Gardens in, Sydney. Albert replied to these accusations and his letters of response are today still held by the National Archives of Australia. In his solid and no-nonsense reply (12th December 1917) he wrote to the Chairman of the New South Wales Wool Committee stating “If in your opinion my charitable action casts the slightest reflection on my position as Appraiser, I am ready to place my resignation unreservedly in your hands”. Such was the character of Albert Reichard. The wealthy family were very keen on horse riding and associated horse sports. All in the family had a love affair with horses. Albert was a patron of the newly established St Ives Showgrounds in the 1920s where horse riding events were the mainstay of events. Until very recently, a large stables complex of unsound structural qualities graced the backyard of Lanosa. Well might you ask, how do all these apparently disjointed threads merge into one tight web? Much of our Council work today is dependent on electronic document ‘systems’. They store all the documents relating to the massive volume of council correspondence – incoming and outgoing emails, letters, council minutes, technical and planning reports and much more. Although Council work is often tedious at times, at other times a few spare minutes may be available for broadening the education – and gaining knowledge of local affairs.

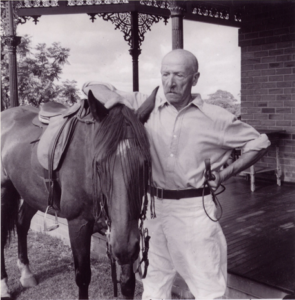

One evening, whilst looking for inspiration, I typed the words ‘German’ into the keyword search of the powerful document system. I was rewarded by a string of results – many with the common word of ‘Reichard’ and ‘Reichard Reserve’. In addition, most of the title lines of the many documents and emails also included ‘Orana Reserve’. Many of the document dates were from a short period during a few months in early 2016. Why such a volume of about a reserve name – and a family with a German name. In my former part of the world, southern Queensland, literally hundreds of street names, parks and reserves were inscribed with memories of days past – when to have a German name, or at least German ancestry, was a link straight to the hard-working teutonic pioneers who had ‘carved farmlands and settlements out of the unyielding, green softwood scrubs’. Such were the folks who made our country. However, obviously, not the case in my new corner of Australia – the leafy and green canopy of the rich northern suburbs of Sydney. In these leafy suburbs great effort was made to retain remnant bushland and today the ‘green canopy’ is loved by all. Most of the early settlers were of English, Irish and Scottish origins – with the very odd smattering of German peoples. I have managed to find a small park reserve, near where I work in Gordon, called ‘Metzlers End’. The German wool buyer Paul Metzler lived in a large house beside the park for a number of years prior to WW2. The few Germans who lived in the northern suburbs of Sydney in the period before the Great War were mainly German wool buyers or businessmen exporting rural produce that originated in the vastness of the outback beyond the hazy Blue Mountains, which are sometimes visible from the high parts of the Hornsby Plateau. After about an hour’s perusal of the many documents, many of them written by historians, councillors and concerned citizens, I soon got the gist of the story. What the issue really was I have summarised below. On Saturday 19th March 1932, the day the magnificently engineered and long-awaited Sydney Harbour bridge was opened, an Irish gentleman named Captain Francis De Groot ‘beat’ the then NSW Labour Premier, ‘big Jack Lang’ to cutting the ribbon by bolting through on a horse and cutting the ribbon with a sabre. Dressed in a regimental hussar’s uniform, De Groot was a veteran of the Great War and a very active member of the ‘New Guard’- a citizen army that would protect the rights of honest and hard-working New South Wales citizens from an essentially left-leaning government. The New Guard had members numbering in the thousands and was largely formed from ex-military veterans. Even the famed and much-loved aviator Charles Kingsford Smith (Smithy) was numbered in their ranks. The New Guard and their many followers were opposed to the left-leaning political views and actions of Jack Lang and were out to thwart him and his government, using force if necessary. On the day Francis De Groot lashed the ribbon with the words “in the name of the decent citizens of New South Wales”, the borrowed horse he was riding belonged to the Reichard family of Pymble. According to historical sources the horse named ‘Mick’ belonged to daughter Margot which she had ridden the day before the big event. According to Margot’s son John Cottee, now a retired resident of Canberra and a published historian, Captain De Groot had been inspired by a cartoon showing a mounted horseman cutting the ribbon with a sword – so he went searching for a suitable mount. Apparently, the wife of Eric Campbell (leader of the New Guard) came across Margot Reichard riding Mick (the horse in question) at Turramurra and then in company with De Groot negotiated with Albert to borrow the horse for use in the proposed venture. Mick was a thoroughbred, standing at 16 and ½ hands high and was deemed to be able to cope with crowds and the noise involved in performing the duties required by De Groot. Mick was certainly considered an ideal find for the mission. However, at the conclusion of the negotiations between De Groot and Albert Reichard, daughter Margot came in with the news that Mick had thrown a shoe – so a farrier was needed. It so happened that the only farrier they could find was a pro-Lang supporter. However, they convinced him that it needed to be done for the opening ceremony (the next day). It seems the ploy worked and the farrier, unsuspectingly, shod the horse! The next day Mick had his moment of glory – or was it infamy. After De Groot’s arrest, Mick was impounded but was returned to Margot in due course. Within the next few weeks the famed and brilliant Sydney photographer, Harold Cazneaux, often called ‘The Quiet Observer’, even came to Lanosa to take a number of lovely portraits of Captain De Groot mounted on Mick. These photographs are now in the possession of grandson John Cottee. Unfortunately in 1933, Mick suffered a broken leg through tripping into a boghole which accidentally finished him off. However, as is often the case in life, there is certainly more to the story! In 1935, the civic-minded Albert Reichard donated a small (one acre) parcel of magnificent wet sclerophyll bushland gully (with huge Sydney Blue-Gum and turpentine trees) to the public of Ku-ring-gai area. He felt this bushland should be preserved for future generations to both see and visit. For decades this small reserve was called Orana Reserve – a generic Aboriginal-based name meaning “welcome”, possibly because of nearby Orana Avenue. According to historian and researcher Sarah McFarlane, The Aboriginal word ‘Orana’, meaning ‘Welcome’, was agreed upon by Albert and Mabel Reichard. As was the word ‘Kywong’, a name formalised by the Reichard family when further subdividing their original land portion. The evidence of this wonderful donation means that this much fragmented and very restricted, endangered ecological community still survives today in a matrix of suburbia. Exactly eighty years later In 2015 a number of civic-minded folks undertook research on Lanosa, the Reichard family history and also the ‘De Groot’ incident. A grandson of Albert, and son of daughter Margot, John Cottee from Canberra, also provided useful information, wrote two small self-published books on family history and the ‘De Groot incident’, and forwarded a small petition in an attempt for Council to rename the reserve. The upshot of this new knowledge was that a move was made to rename Orana Reserve to Reichard Reserve – to honour the families contribution to the history of Pymble and the very far-sighted donation of a piece of beautiful bushland to the community. Council accepted the name change and the NSW Geographical Names Board was notified – and the name change was legally accepted. Until! An old saying is ‘never speak ill of the dead’, as they are voiceless when a defence is required. Such words are not always heeded and in this case a litany of email attacks was then launched on the character of Albert Reichard and forwarded to the councillors – as to whether the family were even ‘worthy’ to be remembered for posterity. Allegations were brought forward that Albert was an abusive man towards his family, a Nazi sympathiser, a conspirator with the anti-Lang government New Guard – and of course had willingly loaned Mick to assist in Captain De Groot’s subversive fascist activities. In addition, the researcher found that Albert had suicided in supposedly suspicious circumstances in July 1941 at Newport, a suburb of Sydney’s northern beaches. In addition the later 1961 suicide in the United States of daughter Suzanne (Sue), who was a respected research psychologist, was brought up as an issue of family instability. The issue of suicide is still a controversial topic, particularly in today’s world where mental health issues are seen as critical. However, in my mind of thought, to use the issue of suicide as an ‘out’ with regard to remembering a families contribution to our society is a lame excuse to deny family memory. What gives even an historian the right, or privilege to determine whether a family becomes recognised – or fades into the depths of obscurity? Whatever the truth – or perpetuated myth – the Council in its wisdom, and to avoid the continued electronic wrath of a vocal minority, bowed to pressure and then re-approached the NSW Geographical Names Board to have the reserve name changed back to the original – Orana Reserve. In true administrative process and procedure the name was reverted – and the Reichard name, with such a fascinating history, will be doomed to public obscurity and lost from recognised landmarks in the area. Albert Reichard was considered a suspicious citizen during the paranoia and hatred of ‘all things German’ during WW1 and was falsely accused of ‘trading with the enemy’. Possibly the extra burden and agony of WW2 was too much for him to face. For instance, in my beloved Toowoomba, Pastor Gutekunst of the Lutheran Church was interned during both wars – as were a number of other German-born pastors and loyal citizens. Nearly all accusations were contrived by over-zealous citizens, intent on damaging the reputation of any person with German connections – either through family or business. Even my very own father and grandad were interned in WW2. However that is yet another story to be told. Albert Emile Reichard walked a rocky road as a German-born wool buyer, even in affluent suburban Sydney. The incidents of 2015, particularly the vicious attack on his integrity showed me that racism is certainly alive and flourishing. The next chapter in my German-Australian research journey will be resurrecting the hidden history of my people. Perhaps like the phoenix, Reichard Reserve will yet have a chance to be known to the public of northern Sydney.

Thank you for this excellent article.

Your story pulls together a treat of remarkable threads. Thankyou.

Thank You Mark for this wonderful insight. I came across some anti German feeling in the 1980s at the Society of Australian Genealogists much to my amusement.