The Whale and Us

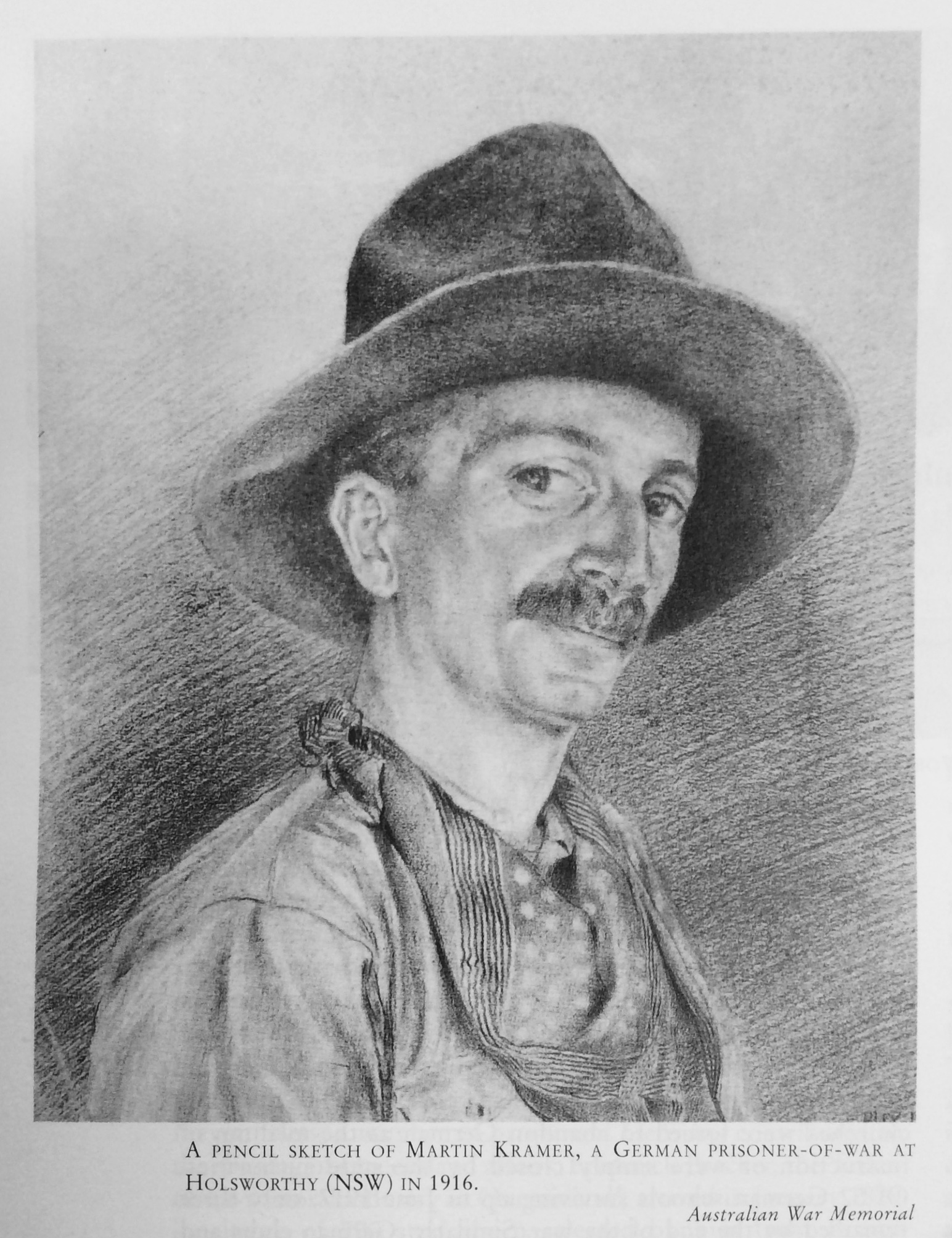

By internee Martin Kramer, Trial Bay Internment camp, 1916

It was 1916 and for myself and 400 other prisoners of war, in the prison camp at Trial Bay in Australia, the war was over. We had been captured from German held islands, from Ceylon to the Fijis and some of us were from the surface raider “Emden”.

Ours was a prison without bars. In fact it needed none. It was hundreds of miles to Sydney through thick uninhabited bush, and the only other route of escape was the wide Pacific – but we had no boats.

We spent our days lazing on the beach and returned to prison at 6 p.m. each day when the gates were locked. They were re-opened at 6 o’çlock each morning. We were all young, healthy young men but somewhat bored with our pleasant but inactive life.

One morning when we were let out, one of the prisoners noticed a dark object out in the bay. As we went down to the beach we saw what the object was.

A stranded whale! The mammal had entered the bay at high tide and had been caught by the ebb, and now lay trapped on a sandbank. It was an unforgettable sight, and to us bored with inactivity, a wonderful diversion.

With a shout, 20 of us rushed down to the beach tearing off our clothes as we ran and began to wade out to the monster.

We swam close up to the whale keeping well away from the deadly tail which thrashed about as the whale tried to free itself.

By now the whole camp, including the commandant, were on the beach. One man bolder than the rest, swam up to the whale until he was touching the towering black sides. Suddenly he pulled himself out of the water, and using hundreds of barnacles as footholds, climbed up to the whale’s back.

Eventually we too screwed up our courage and followed suit, until panting with exhaustion we all stood on the mammal’s back.

We discovered that the whale was about 80 feet long, and the tail fin as far as we could judge, was about 15 feet across. A fellow prisoner, a game warden, estimated its weight to be that of 50 elephants or 200 cattle.

The whale’s eyes were as big as billiard balls and according to a prisoner who later measured them, as hard as ivory.

The whale’s breathing could be heard for a long distance and a tall column of steam came from its blow-hole with a whistling sound.

Gradually our fear of the monster wore off and we began to show our bravado to the onlookers on the beach by capering about the whale’s back. Leaping about, stark naked, we must have looked like a bunch of Lilliputians on a Gulliver.

Suddenly I was struck with an idea. Looking at the smooth shining sides of the whale, it occurred to me that here was a natural slide and I searched for a smooth run where there were no barnacles.

I sat down, pulled my knees up, clasped my shins with my hands, and whoosh! Down I went into the water with a tremendous splash.

That started it. Like a family of otters on a river bank the rest of the men came sliding down. Shouting like a crowd of schoolboys we played follow-the-leader.

Some slid on their backs, others head first and others slid into the water backwards. The whale was our big dipper – no rails, no girls, but the sensation was the same. We carried on like this for some hours until tired out we went back to the camp.

We all realised that very soon the whale would become a malodorous problem, and would make life most unpleasant with its nauseous smell.

Who was the genius who hit on a plan to get rid of the whale, and also to commercialize on its misfortune I can no longer remember, but it was decided that the whale could be killed and the oil from it would in no small way enrich the camp when it was sold.

The camp commandant also became quite enthusiastic about the idea and wired Sydney on our behalf asking what the legal position of the whale was and who owned it. Back came the reply: “Anyone who thrusts the first harpoon into a whale in Australian waters is the lawful owner of it.”

A harpoon. Where on earth could we get a harpoon in Trial bay, surrounded by bush miles from anywhere.

We scoured the camp for a suitable weapon and eventually someone found a length of loose railing on the camp’s disused landing stage. We ripped this loose and after a hard day’s labour we managed to forge it into a sharp enough weapon.

The first man to try to kill the whale was unsuccessful. Several times he lunged at the whale but with no result.

We then picked out the strongest man in the camp – a thickset muscular sailor. Out he waded, holding the harpoon above his head, until he was quite close to the whale. Then he made an almighty thrust with the harpoon and by a stroke of luck hit a vital spot.

The whale’s fountain of steam from its blowhole began to take on a darker colour. From white it changed to pink, from pink to rose and finally to red, until after several hours it died.

We worked like slaves. Using block and tackle and several incoming tides we managed to beach the whale. Working in shifts we manhandled its enormous bulk into a suitable position.

Meanwhile the commandant wired Sydney asking that hundreds of empty four-gallon paraffin tins, tripods, big iron kettles, ladles, solder, tools, sieves and other items should be put on board the camp’s supply ship the next time it came to Trial Bay.

The whole camp threw itself into the work of “Operation Whale”. Even the guards helped. Firewood was collected from the bush and huge stacks of wood grew up on the beach.

Others cut the blubber into strips. We arranged a whale steak dinner for the camp, but this was not a success. The oily taste of the meat put most of us off.

At last the supply ship arrived with all our precious and long awaited equipment. The expense of the equipment (80 pounds) was shared out between us.

We established our boiling down station well away from the camp – a shrewd move because the stench from the whale soon rose sky high.

At first we threw all the residue from the whale into the sea and this attracted dozens of sharks into the bay.

One of our men went for his daily swim and disappeared – taken by sharks. After this we buried all our residue and there were no more swims.

As the smell got worse the camp canteen began to do a brisk trade in Eau de Cologne. As soon as new stocks arrived they were sold out almost immediately. Even the commandant bought some.

Work on the boiling down went on ceaselessly. We worked cheerfully – every man had already spent (in his mind) the fortune he was quite sure would materialise when the whale oil was sold. Hundreds of tins of paraffin were filled, sorted into grades, tested, sealed and stacked awaiting shipment.

We formed a committee to supervise the marketing of the oil.

Finally the work, or rather the whale, was finished. Our tins of oil stood in a great pile ready to be sent off on the next ship. In a few weeks we would all be rich.

But fate had other ideas….

One night we were shaken out of our sleep by the sound of gun-fire. It sounded like a ship firing in the bay!

We could not get out of the camp because the gates were locked and inside pandemonium broke loose. The rumour flew around that a German warship was in the bay and had come to liberate us. Even now a battle was going on.

We were going home! Many of us started packing and I remember polishing my boots so as to be spick and span for roll call.

Anxiously we awaited sunrise.

But in the morning the bay was its usual calm. No warship stood off the shore. No blue-jackets greeted us, all our guards wearing sly grins were in their usual positions.

What had happened? We all heard the gun fire, shot after shot.

Then we saw it. The men who boiled down the whale blubber were no skilled boilers. The oil in the tins had gradually decomposed and expanded until each tin exploded.

Every tin was gone. The beach was a terrible mess and there, soaking in the sand, was the evil smelling liquid which was to have been our fortune.

It took days to recover from this, and weeks before the smell finally left us!

END